|

| |

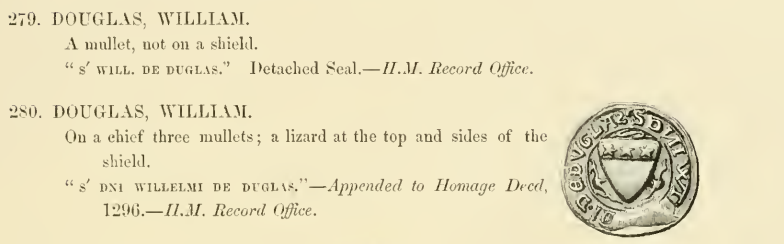

Sir William (le Hardi) Douglas

|

|

|

William “le Hardy”, Lord of Douglas, was the son of

William Longleg, Lord of Douglas and it is supposed by his possible

second wife, Constance Battail of Fawdon(1). He first is recorded at an

Assize at Newcastle-upon-Tyne in 1256, when his father made over a

Carucate of land at Warndon, Northumberland to him. Douglas' father

William Longleg was Lord of Fawdon.

Kindly contributed by Christopher Blyth, volunteer at the

Douglas

Heritage Museum,

With additional material provided by Helen Douglas

This man is a legend in Scottish history and, as a result, his story has

become intertwined with myth. There are elements of his story which we

can reasonably trust to be true. Similarly there are elements of it that

we need to take with a pinch of salt - and others that we can comfortably

reject.

What we do know is that he was born (most likely in 1243) and most

likely as the second child (and second son) to William Longleg of

Douglas. However his older brother (Hugh) died sometime around the same

time as their father (who we know died in 1274) – we do not know if

Hugh, however briefly, inherited his father’s title before he passed.

Nevertheless we know that very soon after Longleg’s death, William had

inherited the estates and titles of his father. He was certainly in

charge by 1279. And within the following years he was knighted (at

latest, in 1288).

Some brief context of the family:-

William Longleg was the descendant of noblemen (probably from Flanders)

who had been invited to come to Scotland by David I. The lands of

Douglasdale most likely fell under the jurisdiction of the lordship of

Galloway at this time. Through working for the Lords of Galloway (who

helped put down several uprisings and rebellions against the Scottish

Crown) the owners of Douglasdale grew in power.

Similarly they also obtained land and titles in

Moray, probably as a

result of helping Galloway put down a rebellion by the MacUilleam in the

1160’s.

Longleg’s wife (Le Hardy’s mother) was a noblewoman from

Fawdon in

Northumbria. You may have read that Longleg also married a noblewoman of

Carrick (a relative of Robert Brus). This is most likely a fabrication;

a later invention to solidify the already-strong bonds between the Brus

and the Douglas families.

Le Hardi’s life:

I will detail below what we know of Le Hardi’s life before his father

death, and then what we know of him after he inherited his father’s

titles.

William Le Hardi is first mentioned in historical records in 1256, where

he is granted land at Warndon (in the family Northumbrian lands) for his

“homage and service”. We was probably 13 years old at the time (this was

possibly a ‘coming of age’ gift). About a decade later, Longleg bought

out the Fawdon estate from his wife’s family. However as a vassal to the

Earl of Angus, the Douglas family had to pay rent to their liege lord,

Gilbert De Umfraville.

Umfraville took Longleg to court for alleged unpaid rents, but a jury

acquitted Douglas. Umfraville took 100 men and attacked the Northumbrian

estate, taking the law into their own hands. This event has been dated

to July 19, 1267. In the fighting someone made an attempt on the young

William Douglas’ life (he would be about 24 by this point). The

historical record details that the attempt was made to strike his head

clean off. We know it must have been a severe wound (it wouldn’t have

been mentioned so much if it was not) which he received (on the neck)

during the fighting. Umraville, we can safely say, won that fight: his

men made off with about £100 in goods.

You may read that this event has been mistranslated. It has been written

elsewhere that the reference to a head being struck off is a reference

to an attempt to strike down the head of the family. I don’t know where

this notion came from but in my view it is inaccurate: William at this

time was not the head of the family, he was a second son. The father was

carried off and imprisoned at Harbottle Tower and young Douglas was

left, likely, for dead.

We know, however, that he survived: this is possibly how he got his name

“the bold” although that is an assumption - we do not know for sure.

There is a possibility that Le Hardi took part in the battle of Largs

in

1263 (aged circa 20 years old): there is some vague reference to two of Longleg’s sons taking part in that battle. If this record is accurate it

is most likely a reference to Hugh and William.

It is important to remember that the Douglas family was a relatively low

ranking noble family. Males would be primarily concerned with two

things: the running of estates… and war. From a very young age these

men, le hardi included, would have been trained and raised to be a

fighter. They would have learned horse riding (although, it is unlikely

they would have been encouraged to fight on horseback, that was a rarity

in Scotland at the time) as part of this training.

There is some reference to one of the Williams going on crusade (the 8th

crusade). This is possibly a historical invention. The original

recording is a reference to someone else’s work that William Longleg

went on crusade. This is possible. But there is a possibility that it

was the son who went instead (second sons often went on such ventures).

We simply do not know. However, there is said to be (or was) a seal in

the Selby deeds that was affixed to a contract of sale for Le hardi's

lands so that he could travel to the Levant as a Squire in the

retinue of Earl Adam.

By the 1280’s we know that Le Hardi was running his inherited estates,

and had been knighted (by 1288). In 1288 he was called upon by Andrew de

Moray (who outranked the Douglasses and would have exerted some

influence on them, being the lord of Moray where they held land and

titles). Moray wanted Douglas to imprison a man wanted for the murder of

one of Scotland’s guardians. That man was Douglas’ uncle, Hugh de

Abernethy. In those days kinship counted for much of one’s loyalties but

Douglas nevertheless imprisoned his own uncle for Moray. The De

Abernethy died whilst imprisoned at

Douglas Castle by William (he was

imprisoned there for around 4 years, but no later than 1293). This

angered Edward of England (this would become a regular feature of

Douglas’ life) who had requested Abernethy’s transfer to his own

custody. Douglas had refused that order (which came in 1291, so

presumably, more than a year passed between the order and Abernethy’s

death in Douglas’ custody).

During that time we first see William styling himself as Lord of Douglas

(first recorded in 1289). This is a promotion in the pecking order and

possibly came as a result of his obeying ‘law and order’ over kinship.

We do not know when, but at some point in the 1270’s or (more likely) in

the early 1280’s, Douglas married Elizabeth Stewart (her father was a

guardian of Scotland). Again this shows the rising status of the family.

She bore William their son James (later styled 'Black' and 'Good') in

1286. She died at some point in the next two years, probably in child

birth. He would not be wifeless for long however.

In 1288 Eleanor Ferrers de Louvain(2), recently widowed, came North to

Scotland to collect her dead husband’s rents from their lands here. She

was a very influential and highborn woman. He father in law was the earl

of Derby and her father was descended from the Count of Louvain. Being a

widow of such high status (and in possession of such large tracts of

land) Edward of England took a personal interest in her search for a suiter.

Whilst in Scotland she stayed at Fa’aside Castle near Tranent in the

Scottish borders. William Douglas, alongside a local knight (John

Wishart) abducted Eleanor and took her to Douglas Castle. She doesn’t

seem to have minded. They were wed very soon afterwards (And she would

even pay his bail in future to spring him from jail - being a bit of a

rogue he was prone to getting arrested).

Edward was again annoyed. The Northumberland lands were seized and

demands made to the guardians of Scotland to arrest Douglas and deliver

him (and his new wife) to him. However one of the guardians was his own

brother in law (James Stewart) and Alexander Comyn was Eleanor’s.

Edwards demands fell on deaf ears.

Nevertheless, in 1290, William was arrested by agents of the English

Crown (a warrant had been out for his arrest since 1288/9) and was held

prisoner at Knaresborough Castle. This imprisonment does not appear to

be harsh. He was released by the spring of the same year, when his wife

Eleanor posted bail for his release in May of 1290 along with four

manucaptors, these four Knights all being Eleanors cousins. John

Hastings, the 1st Baron Hastings, Nicholas de Segrave, the 1st Baron

Segrave, William de Rye and Robert Bardulf who had acted as guarantors

for his release. In the process of this Eleanor was fined £100 sterling

and had some of her manors in the South of England seized (they were in

English hands by 1296).

In 1291, Douglas swore fealty to Edward of England, who was in Scotland

to act as arbitrator for the selection of a new king in Scotland.

However within months he had fallen out of favour with the King of

England again and this time his lands in Douglasdale were seized.

Once a new king was found (John Balliol) in 1292, Douglas was in trouble

with him too. He, and other notables such as Robert Brus, failed to

attend the new king’s first parliament in February 1293. The Crown sent

royal officers to his estate (by this point they were restored) in

Douglasdale but he imprisoned them there and refused their orders. He

attended Balliol’s second parliament, and was arrested for this.

In 1295, Douglas was one of the Scottish nobles to rebel against Balliol

and set up a new guardianship. His military experience and his rising

rank are highlighted here by the fact that he was given the title of

governor of Berwick by the new guardianship. The town was the most

important commercial hub in Scotland at the time and a key strategic

position, being one of the only crossings an invading Army could use

across the Tweed river.

|

| William was initially the only Scotsman of rank who refused to sign the Ragman Roll. However, he was to sign it twice in 1296. The first time was in Edinburgh on 10th June and the second was on 28th August in Berwick on Tweed |

|

| William's initials 'WD' on the wall of the Beauchamp Tower,

carved while he was held prisoner in 1297 |

Edward marched on Berwick and sacked the town on Good Friday 1296. The

defenders in the Keep soon surrendered and William was imprisoned, the

last of his lands in Essex were seized and his son was taken as a

hostage (2-year-old Hugh, his eldest son to Eleanor with Archibald being

born later). At this point James, the elder son, was probably in France.

He was imprisoned until he signed the Ragman Roll (like most scots

nobility), thus pledging fealty to Edward. His lands in Scotland were

restored but not those in England. And the Northumbrian estate was given

to the man who had nearly decapitated him years before (Umfraville).

In 1297, Douglas, alongside fifty other Scots nobles, was ordered to

accompany Edward on Campaign in France. He refused - by this time

Wallace had rebelled. Wallace was from Lanark, a mere 12 miles from

Douglasdale. The two campaigned together briefly, winning success

against Edward’s forces in Scotland.

It has been supposed that it was whilst he was in the midst of raiding

Douglasdale (for Edward, in retribution for this uprising) that Robert

Brus switched sides. He was accompanied by the Lady of Douglas and the

local warriors to Irvine where the rebels were meeting. This is a good

story, and quite possibly true. But the evidence for it is lacking.

William was the first nobleman to join with Sir William Wallace in 1297

in rebellion; combining forces at Sanquhar, Durisdeer and later Scone

Abbey where the two liberated the English treasury. With that booty

Wallace financed further rebellion. Wallace joined his forces with that

of Sir Andrew Moray and together they led the patriot army in the Battle

at Stirling Bridge fought on 11 September 1297. They were joined by

other patriots such as Robert Wishart Bishop of Glasgow, and the Morays

of Bothwell, with a contingent of Douglases at the national muster at

Irvine, North Ayrshire.

By June 1297, Wallace was in central Scotland with Andrew De Moray.

Their rebellion was in full swing. William Douglas was at Irvine with

other Scottish nobles who were in open rebellion too. However they could

not agree on anything and with the English army cresting over the hill,

their forces began to abandon their position and go over to the English.

William and his comrades were soon left with little choice but to

‘capitulate’. He was again imprisoned as a result of this. First he was imprisoned at

Berwick Castle, in what is now known as the Douglas Tower, and then sent

to the Tower of London (After the English defeat at

Stirling Bridge). He

died there within a year.

The historical record points to Edward’s hate for Douglas being so

furious that his eldest son James (later known as the Black) was the

only Scottish noble not to have his family lands given back to him after

swearing fielty to Edward (after the defeat at Stirling Castle). This

put James in the unenviable position of being a landless knight and

forced him into open hostility against Edward: hence his allegiance with

Robert Brus’ later rebellion. Edwards hate of William Le Hardi,

therefore, put Le Hardi’s son on the path which led to Edward’s (and his

son’s) defeats in Scotland.

If James Douglas had been given his father’s lands back, it is possible

he would not have joined Robert’s rebellion. And it is therefore likely

that said rebellion would have ended with a very different outcome.

Notes:

1. Through the marriage of

William le Hardi to Eleanor de Lovaine, the Earls of Douglas could trace

their ancestry to the Landgraves of Brabant. In the story of Sholto

Douglas, his son William Douglas is a commander of forces sent by the

mythical Scottish king Achaius (Eochaid?), to the court of Charlemagne

to aid him in his wars against Desiderius, King of the Lombards. William

Douglas is said to have settled in Piacenza where his descendants became

powerful local magnates under the name Scotti (or Scoto), and eventual

leaders of the Guelf faction of that city.

Read more>>>

Eleanor was the

daughter of Matthew de Lovaine , Lord of Little Easton, Seneschal of the

Honour of Eye (Eye Castle, Essex) (b. about 1202 in Little Easton,

Essex, England – d. 1 June 1258 in Little Easton, Essex, England),

himself the grandson of Godfrey III (Dutch: Godfried; c. 1142 – 21

August 1190), Ccount of Louvain (or Leuven), landgrave of Brabant,

margrave of Antwerp, and duke of Lower Lorraine (as Godfrey VIII) from

1142 to his death.

See also:

1.

Constance de Flamville and her heirs |

Source

Sources for this article include:

Fraser, Sir William. The Douglas Books. Edinburgh, 1885

Any contributions will be

gratefully accepted

|

|