DOUGLASS, HENRY GRATTAN (1790-1865), doctor of medicine and public

servant, was born in Dublin, a son of Adam Douglass, apothecary, and his

wife Ann, née Edwards. His grandfather was Adam Douglass of Killensule,

County Tipperary. He saw service as an assistant surgeon with the 18th

Regiment in the Peninsular war in 1809-10 and in the West Indies in

1811. Invalided home in 1812, he took a civil appointment as medical

superintendent of the Fever Hospital and Infirmary at Cahir, Tipperary.

In 1815 he was admitted a member of the Royal College of Surgeons of

England and in 1819 became a licentiate of the King's and Queen's

College of Physicians of Ireland. In 1817 he returned to Ireland during

an epidemic of typhus and later published a pamphlet on

The Best

Means of Security Against the Prevailing Epidemic, and a thesis on

typhus which he submitted for the doctorate of medicine of Trinity

College, Dublin. In June 1820 he was elected to the Royal Irish Academy,

a great honour at his age.

Douglass arrived in Sydney in May 1821 with his family and a letter

of introduction from Bathurst to Governor Macquarie, who placed him in

charge of the general hospital at Parramatta. He entered into colonial

life with enthusiasm and soon became a member of the Agricultural

Society, a vice-president of the Benevolent Society and first secretary

of the Philosophical Society, the first local organization to foster

Australian science. In addition to his hospital work at Parramatta, he

was superintendent of the Female Factory and had a private practice. A

good house was rented for him by the government until new quarters could

be built, and he was appointed a magistrate.

When Governor Brisbane arrived in November 1821, Douglass became a

regular visitor at his residence. This association brought him into

conflict with his senior colleagues on the Parramatta bench. The first

clash came in August 1822 over a convict girl, Ann Rumsby, whom he had

taken into his home; Dr James Hall, surgeon superintendent of the

Maria Ann in which she had been transported, alleged that Douglass

was behaving improperly with her. Samuel Marsden, Hannibal Macarthur and

three other magistrates held a meeting, to which Douglass was summoned

but failed to appear. The magistrates then had Ann arrested, and for

perjury she was sentenced to imprisonment at Port Macquarie. Brisbane

intervened, gave her a free pardon, threatened to remove the Parramatta

magistrates who had not only refused to sit with Douglass on the bench

but also called a secret general meeting of justices to support their

action, and complained to London of a conspiracy against Douglass.

Douglass, however, soon showed that he could fend for himself. In April

1823 he brought an action for libel against Hall, claiming damages of

£5000, and was awarded £2 and costs. Next month with William Lawson he

fined Marsden for allowing one of his convict servants to be at large

and, when he refused to pay, had his piano seized and sold. Marsden

promptly sued him for damages of £250, but the court awarded him only

the amount of the fine. Marsden then complained to the bishop of London

that Douglass was preventing inmates of the Female Factory from taking

their infants to church for baptism, and connived with Hannibal

Macarthur in a letter to Robert Peel at the Home Office, charging

Douglass with drunkenness, torture of prisoners and other disreputable

official conduct. These letters, forwarded to the Colonial Office,

brought orders for an inquiry which exonerated Douglass but provided a

loophole for Macarthur as foreman of the Grand Jury to publish further

complaints against Douglass in the Sydney Gazette. Brisbane's

reports extolled his virtues with increasing warmth after each attack

and in February 1824 he nominated him as commissioner of the Court of

Requests and sent him to London to consult the Colonial Office on the

functions of the new court.

Bathurst was impressed and suggested his appointment as clerk of the

Legislative Council, but soon had a change of mind when Douglass was

censured for a gross breach of military discipline. Inquiry revealed

that he had left England in 1821 without permission and that the War

Office, after tracing him with much difficulty, had received from him no

answers to their letters; recalled for service in March 1825, he sailed

for Sydney again without apology or explanation, thereby forfeiting his

half-pay. Other doubts assailed Bathurst when he heard rumours that

Douglass had been foisted on him 'by the interests of a certain party in

England vulgarly known as “the Saints” ', and that Archdeacon Scott

threatened to resign if Douglass were appointed to the Legislative

Council. Brisbane was obliged to agree that 'a considerable proportion

of the Community' was hostile to Douglass and persuaded him to resign as

a magistrate. After Brisbane's departure in 1825, Douglass fell further

from grace. Governor Darling resented his intrigues and moved him back

and forth between the council and Court of Requests. After injudicious

remarks at a Turf Club dinner and at a public meeting he was suspended

in December 1827, Darling reporting that he was too mischievous for

public office. The Colonial Office thought Darling's reasons were

trivial and persuaded him to send Douglass to England for six months on

half-pay.

Douglass left Sydney in May 1828. Followed by warnings that he would

act in England as agent for Wentworth's party, he soon lost favour at

the Colonial Office and was refused further colonial appointment. In

1829 he sued the editor of the Sydney Gazette for libel and was

awarded damages of £50. Later he heard that his land grant at Narrigo on

the Shoalhaven River had been cancelled. This land and his son's farm at

Camden had been leased in 1828 to Wentworth for three years, and

thereafter he had trouble in finding agents. In 1839 he sought

compensation from the Colonial Office, but after long correspondence his

claim was rejected; in spite of a strong letter from Brisbane, Governor

Gipps could trace no record of Douglass's authority to occupy the grant,

although he did unearth proof of a seventeen-year-old debt to the

colonial government of more than £700.

In 1835 Douglass was a physician extraordinary attached to the King's

household, but he soon left England for France. In Paris his knowledge

of infectious disease was valuable during an epidemic of cholera, and

his services won commendation and a medal from the government of Louis

Philippe. In a suburb of Le Havre he founded a seamen's hospital and

directed it for twelve years. He returned to Sydney in October 1848 as

surgeon superintendent of the emigrant ship Earl Grey, loud in

protest that the sending of his Irish female charges was 'a gross

imposition on the Land and Emigration Commissioners'. Next year he

became an honorary physician at Sydney Hospital and thus was one of the

first teachers of clinical medicine in Australia. In 1854 he was

appointed a director of the hospital, but resigned after two years to

take a seat in the first Legislative Council under responsible

government. His bill to regulate the qualifications of practitioners in

medicine, surgery and pharmacy was laid aside in 1860. He also resumed

his philanthropic activities, becoming medical officer of the Benevolent

Society, and helping Charles Nicholson to revive the Philosophical

Society which was soon renamed the Royal Society of New South Wales. He

also helped to introduce child welfare by sharing actively in forming a

Society for the Relief of Destitute Children and in establishing an

orphanage at Randwick for their care. Douglass played an early part in

the founding of Sydney University. F. L. S. Merewether, an original

senator and later chancellor, wrote of him: 'Shortly after his return to

the colony, the foundation of an University became apparently the chief

object of his thought, and he discoursed on it frequently and

earnestly'. Douglass badgered Merewether and other officials; they

advised him to seek the advocacy of W. C. Wentworth, who had already

shown interest in the matter. Wentworth was successful, but Douglass was

not appointed to the first university senate. He was elected to fill a

casual vacancy in 1853 and upheld, without much success, a policy of

expansion. He was a member of the medical faculty committee and remained

a senator until 1865.

Douglass died in Sydney on 1 December 1865, at the age of 75, and was

buried in the Anglican churchyard at Camden. In 1812 in Dublin he had

married Hester, daughter of Arthur Murphy, chief of O'Murrough in County

Wexford, and his wife Margaret. They had a son and two daughters.

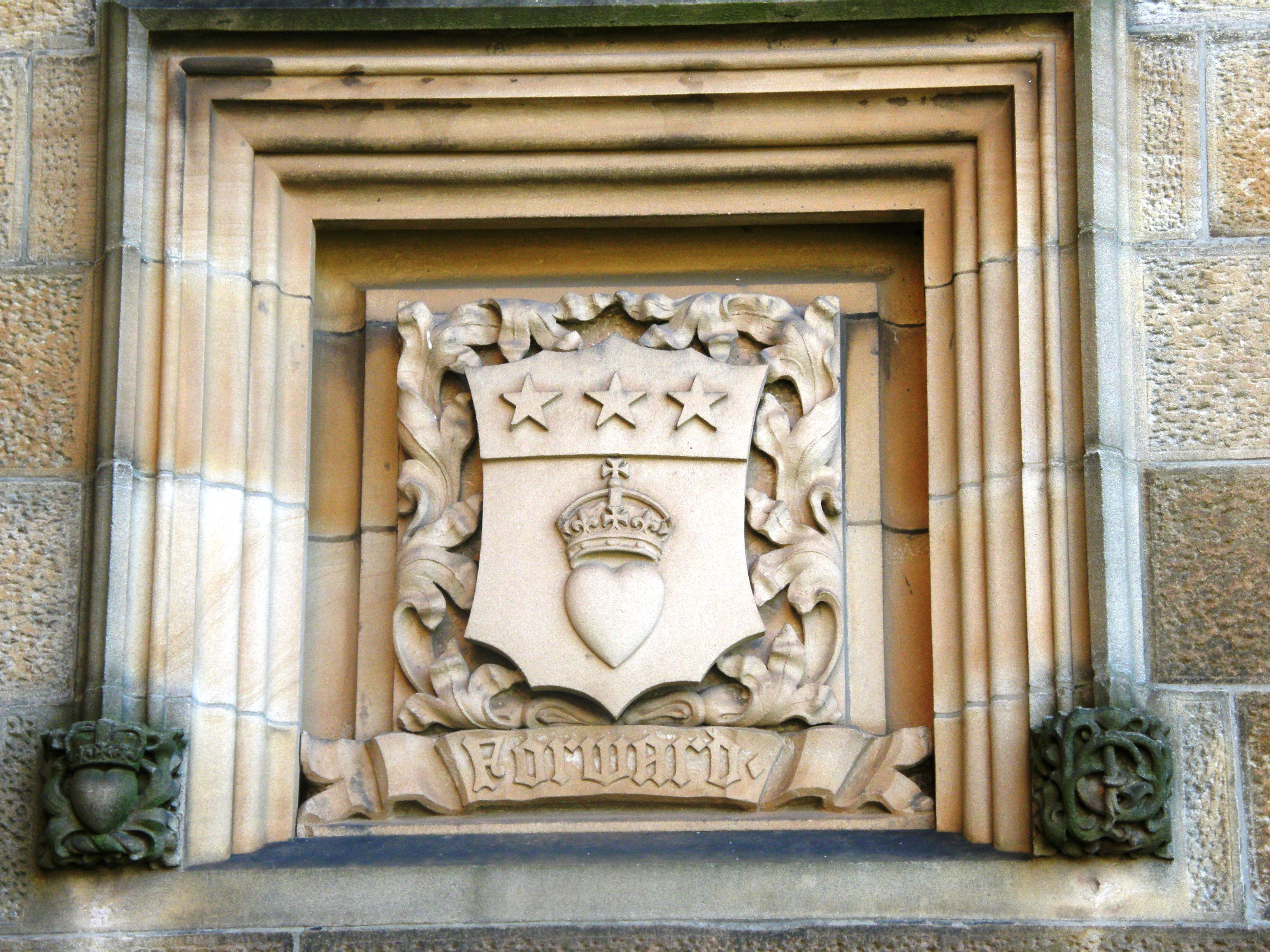

Douglass is commemorated at the University of Sydney by his coat of arms

in stone on the south side of the entrance to the Great Hall, and in a

stained glass window in the south porch of the main building.