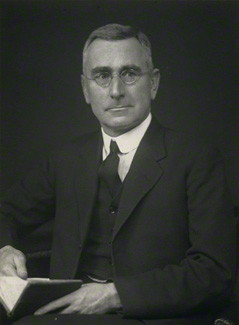

Claude Gordon Douglas

Claude Gordon Douglas(1882–1963), physiologist,

was born in Leicester on 26 February 1882, the second son of

Claude

Douglas, honorary surgeon to Leicester Royal Infirmary, and his

wife, Louisa Bolitho Peregrine, of London. Both his grandfathers

were also in medical practice: James Douglas, L.R.C.S. (Edin.), was

Consulting Surgeon to the Infirmary in Bradford and Thomas

Peregrine, M.D. (Edin.), M.R.C.P. (London), was in practice in

London.

Claude Gordon Douglas(1882–1963), physiologist,

was born in Leicester on 26 February 1882, the second son of

Claude

Douglas, honorary surgeon to Leicester Royal Infirmary, and his

wife, Louisa Bolitho Peregrine, of London. Both his grandfathers

were also in medical practice: James Douglas, L.R.C.S. (Edin.), was

Consulting Surgeon to the Infirmary in Bradford and Thomas

Peregrine, M.D. (Edin.), M.R.C.P. (London), was in practice in

London.

His elder brother, J. S.

C. Douglas, was professor of pathology at Sheffield University, and

his cousin, J. A. Douglas, was professor of geology at Oxford. He

was a scholar at Wellington College, but moved to Wyggeston grammar

school, Leicester, to study science. In 1900 he went up to Oxford,

where he was a demy of Magdalen College. In 1904 he obtained

first-class honours in natural science (animal physiology), after

which he stayed on in the physiological laboratory, working for the

research degree of BSc under the supervision of J. S. Haldane. In

1905 Douglas took up a London University scholarship at Guy's

Hospital and completed his medical degree of BM, BCh (Oxon.) in

December 1907. Six months earlier he had been elected to a

fellowship and lectureship in natural science at St John's College,

Oxford, a position he held for forty-two years. He became DM in

1913.

Douglas's scientific career falls into three parts: the

first, his collaborative work up to 1914 with J. S. Haldane on human

breathing; the second, his work during the First World War on

physiological aspects of gas warfare; and the third, back in Oxford,

after Haldane's departure from the physiological laboratory, on

general human metabolism, successively as university demonstrator

(1927), reader (1937), and titular professor (1942), and, after he

had passed the retiring age, as departmental demonstrator up to

1953.

It was Douglas's good fortune to join the physiological

laboratory when work on the regulation of body oxygen and carbon

dioxide concentrations, and exchange of these gases through the

lungs, was still developing. He quickly became the best-known and

the most permanent of the younger colleagues of Haldane, whose work

since the turn of the twentieth century had transformed the subject

of respiration. Douglas's name appears on some ten of the most

important papers over this period, which show an insight into the

principles of control physiology three or four decades ahead of

their time. Douglas and Haldane provided a quantitative description

of the transport of carbon dioxide by the blood between cells and

lungs, and the facilitatory effect on it of oxygen transport in the

opposite direction. This work complemented the earlier work of

Christian Bohr, K. A. Hasselbalch, and S. A. S. Krogh, of

Copenhagen, who had shown the facilitatory effects of carbon dioxide

on oxygen transport. Work of this kind allowed Douglas and Haldane

to develop a practical and bloodless method for measuring the rate

of pumping of blood by the human heart under various conditions.

Detailed and meticulous measurement allowed Douglas and J. S.

Haldane (with some mathematical assistance from J. B. S. Haldane) to

elucidate the equilibria between the oxygen-carrying substance

haemoglobin and the concentrations of oxygen and carbon monoxide.

They went on to show that certain conditions, notably residence at

high altitude, altered the equilibria. Ingenious reasoning led them

to conclude from this observation that oxygen could be transported

against the concentration gradient across the lung capillary

membranes (oxygen secretion). The question was open at the time, and

the resulting controversy between them and their friends Krogh and

Joseph Barcroft, of Cambridge, was one of the entertainments of

early twentieth-century physiology. Subsequent developments decided

the controversy against Oxford, but the basic observation remained

unexplained.

During this period Douglas began to measure the

rate of uptake of oxygen and of the output of carbon dioxide by

collecting expired air in a large canvas gasbag. The Douglas bag

became well known for its convenience for measuring energy

expenditure in people in various occupations.

Douglas served

in the Royal Army Medical Corps in the First World War, reaching the

rank of lieutenant-colonel. When gas warfare started in 1915, he was

the serving officer in France with the detailed knowledge and deep

understanding of respiratory physiology that allowed interpretation

of the effects of the alarming new weapon. He held several

appointments in the British expeditionary force related to gas

warfare before being appointed physiological adviser in 1917 to the

Directorate of Gas Services, where he worked with Harold Hartley. He

was awarded the MC in 1916, was four times mentioned in dispatches,

and was appointed CMG in 1919. He contributed extensively to the

official history of the war, and Hartley felt that his chapter

dealing with the development of gas warfare was by far the best

summary of the use of the new weapon.

After the war Douglas

returned to Oxford, where he collaborated with J. G. Priestley in

setting up and running a novel and thorough practical course in

human physiology. The course was taken by all Oxford medical

undergraduates over a period of some thirty years.

After J.

S. Haldane left the physiological laboratory, Douglas's interests

moved towards the assessment of metabolic processes in humans in the

light of the new insights provided by the rapid expansion of

biochemistry. With a succession of research students, including F.

C. Courtice, he applied the new knowledge to the interpretation of

quantitative measurements. His conclusions put him in the vanguard

of those who questioned the fashionable, though erroneous, view that

carbohydrate was the sole source of energy for muscular contraction.

Between the wars the departure of Haldane and the scanty material

support received by his branch of physiology rendered difficult any

achievement in his field of interest; the Oxford laboratory was more

concerned with the exciting advances in neurophysiology of the

school of C. S. Sherrington.

During the Second World War

Douglas remained in Oxford, teaching and helping with administration

in college and the laboratory. After the war and before his final

retirement in 1953 he supervised the work of three more research

students, including Roger Bannister.

From 1920 onwards

Douglas was increasingly involved in government committee work, some

of which he took over from J. S. Haldane, on such topics as chemical

warfare, muscular activity in industry, health and safety in mines,

conditions in hot and deep mines, research on pneumoconiosis,

breathing apparatus for the National Fire Service, the Gas Research

Council, heating and ventilation of buildings, and diet and energy

requirements. As a chairman or member, Douglas prepared his papers

meticulously, listened carefully, but spoke comparatively seldom.

Douglas was a devoted senior member of St John's College, which

was his home for twenty-eight years. He was a formidable walker, and

a keen and very knowledgeable gardener and photographer. He was an

excellent host in college and at home. Douglas was unmarried and

lived with his younger sister, Margaret Douglas, for twenty-four

years.

In 1911 Douglas won the Radcliffe prize; in 1922 he

was elected FRS and was on the council of the Royal Society

(1928–30). He was an ad hominem professor at a time when

Oxford had few such. In 1945 he was awarded the Osler memorial

medal, and in 1950 he was elected to an honorary fellowship of St

John's.

Douglas's early and best-known joint work in academic

physiology probably stemmed in large part from Haldane's genius.

However, his extraordinarily high standards of accuracy, his energy,

his rare common sense and general competence must have contributed

greatly to the joint achievement. His capacity as an independent

scientist was obvious to his younger colleagues and to readers of

his writings on chemical warfare.

Douglas died in the

Radcliffe Infirmary on 23 March 1963 after a street accident in

Oxford.

See also:

•

Family history of James Robert Douglas; contains several family

trees [pdf]

Errors and Omissions

|

|

The Forum

|

|

What's new?

|

|

We are looking for your help to improve the accuracy of The Douglas

Archives.

If you spot errors, or omissions, then

please do let us know

Contributions

Many articles are stubs which would benefit from re-writing.

Can you help?

Copyright

You are not authorized to add this page or any images from this page

to Ancestry.com (or its subsidiaries) or other fee-paying sites

without our express permission and then, if given, only by including

our copyright and a URL link to the web site.

|

|

If you have met a brick wall

with your research, then posting a notice in the Douglas Archives

Forum may be the answer. Or, it may help you find the answer!

You may also be able to help others answer their queries.

Visit the

Douglas Archives Forum.

2 Minute Survey

To provide feedback on the website, please take a couple of

minutes to complete our

survey.

|

|

We try to keep everyone up to date with new entries, via our

What's New section on the

home page.

We also use

the Community

Network to keep researchers abreast of developments in the

Douglas Archives.

Help with costs

Maintaining the three sections of the site has its costs. Any

contribution the defray them is very welcome

Donate

Newsletter

Our newsletter service has been temporarily withdrawn.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|