The Douglas Cause

In the mid 18th century the outcome of a law case gripped the

nation. It led to death threats, riots and the equivalent of £150m

was bet upon its outcome. This was the Douglas Cause.

Had

Archibald, the Duke of Douglas, not been a duke and the owner of

vast swathes of Scotland, history would not have heard of him. He

was virtually illiterate, took no part in the affairs of the nation,

lived as a recluse, died childless and may well have been insane. In

order to ensure the loyalty of the Douglases to the new regime, his dukedom

came from Queen Anne when he was aged nine. His heir was his sister

Jane and, should she fail to produce offspring, the duke’s fortune

and most of his string of ancient titles would pass to his cousin,

married to the Duchess of Hamilton. All looked set fair for the Hamiltons. Both Jane and her brother were unmarried, at least until

1746 when she made an unsuitable union with Colonel John Stewart, a

Jacobite sympathiser. But that did not seem to be a problem for the

Hamiltons since Jane was 48.

The couple went to the Continent

and, two years later, Jane claimed to have given birth in Paris to

twin boys, Archibald and Sholto.

Encouraged by the Hamiltons,

her brother refused to recognise the boys as her children and his

heirs. He cut off his sister’s allowance and when the couple

returned to Britain in 1751, Stewart was imprisoned for debt. Jane

and her son Sholto both died in 1753 and young Archibald ended up in

the care of the Duke of Queensberry who saw to his education. To

general astonishment Douglas married in 1758. Three years later and

only 10 days before he died his duchess managed to persuade him to

accept Archibald as his heir.

Archibald changed his name from

Stewart to Douglas and, after a brief legal tussle with the

Hamiltons, he duly entered into his inheritance, then worth the

remarkable sum of £12,000 a year.

With so much at stake, it

was unsurprising that the Hamiltons objected. They sent a 'shady

investigator' to Paris who came back with the information that

Archibald was actually Jacques Louis Mignon, son of a glassworker,

who had been kidnapped in July 1748 by ‘a Lady, a Gentleman and

their maid’, that Sholto was the son of Sanry the Rope Dancer who

had vanished in similar circumstances. The 'gumshoe' (1) also reported

that the whole story of Jane’s pregnancy was a fraud, that witnesses

to it could not be found, that the couple had not stayed where they

said they had.

In 1762, the Hamiltons launched an action in

the Court of Session in Edinburgh claiming that Archibald was no

Douglas and had no right to the inheritance and that it was absurd

to claim that Jane could have had twins at 51. By 1767, at the

request of the judges, each side had published memorials - 1,000

page statements of their cases, containing letters, documents,

witness reports, affidavits, citations of Scots and French law and

anything else that the lawyers could think of. For the legal

profession the case was a bonanza, lasting eight years and racking

up costs of £52,000 before it was resolved. Litigation took place in

Scotland, England and France with immense public interest throughout

Europe being taken in every stage of the process.

Everyone

had an opinion and everyone took sides. David Hume, Adam Smith and

Dr Samuel Johnson all supported the Hamiltons. Johnson’s biographer,

James Boswell, disagreed and became a propagandist for Archibald’s

faction, producing more than 20 articles and three books on the

subject. He had the Edinburgh mob on his side.

Amid intense

interest, a total of 24 lawyers read speeches to the 15 judges

before whom the case was heard. The speechifying lasted 21 days,

making it the longest ever pleading before the Court of Session. On

14th July 1767, the Court gave its opinion. The judges were split

down the middle, seven in favour of the Hamiltons and seven for

Archibald.

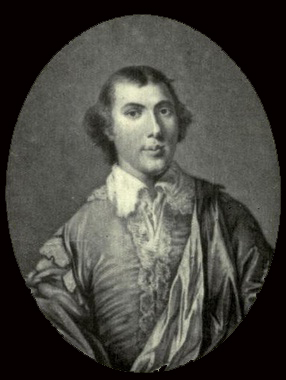

|

| Archibald, 1st Lord Douglas |

The Lord President, Robert Dundas, gave a casting

vote in favour of Hamilton. As one contemporary observer, lawyer

Robert Stewart wrote ‘poor Douglas lost his cause yesterday by the

president’s casting vote, leaving him without father or mother,

sister or brother or any relation on Earth for the evidence on which

he is condemned does not give him in law other parents’.

Archibald’s lawyers immediately launched an appeal to the House of

Lords in London. Apart from anything else £100,000’s worth of bets

depended on the outcome, perhaps £150 million in today’s money. The

case opened in January 1769 and lasted over a month. During its

hearing, the private detective challenged and fought a duel against

one of Archibald’s lawyers who had called him a liar. Pistols were

fired but both missed. The decision was unanimously reversed and

Edinburgh went wild with joy.

The judges who had opposed

Douglas had their windows smashed and the mob plundered the Hamilton

apartments in Holyrood House. For two days it was dangerous for

opponents of Archibald to be in Edinburgh. Then troops were ordered

to the city and order was restored.

The dukedom died with

Archibald’s uncle but the young man became one of the richest

magnates in Scotland, owning land in Wiltshire as well as eight

counties north of the border.

He was an improving landlord,

married twice into ducal families and entered politics as MP for

Forfarshire. In 1782 was raised to the peerage as Baron Douglas of

Douglas in 1790. After an unexceptional life he died in 1827 aged

79.

In a corollary to the story, in 2008 letters were found

in the archives of the Earl of Home written by Archibald’s mother

Jane and one of her lawyers. They strongly indicate that she and her

husband did actually buy the babies in Paris.

Notes:

1. The 'gumshoe' was Andrew Stuart of Castlemilk and

Torrance. He was engaged by James, sixth duke of Hamilton, as tutor

to his children, and through his influence was in 1770 appointed

Keeper of the Signet of Scotland. When the famous Douglas lawsuit

arose, in which the Duke of Hamilton disputed the identity of

Archibald James Edward Douglas, first baron Douglas, and endeavoured

to hinder his succession to the family estates, Stuart was engaged

to conduct the case against the claimant. In the course of the suit,

which was finally decided in the House of Lords in February 1769 in

favour of Douglas, he distinguished himself highly, but so much

feeling arose between him and Edward Thurlow (afterwards Lord

Thurlow), the opposing counsel, that a duel took place. After the

decision of the case Stuart in 1773 published a series of Letters to

Lord Mansfield (London, 4to), who had been a judge in the case, and

who had very strongly supported the claims of Douglas. In these

epistles he assailed Mansfield for his want of impartiality with a

force and eloquence that caused him at the time to be regarded as a

worthy rival to Junius.